Research in ASV therapy

Get the big picture of adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) therapy, with an overview of updated guidelines and evidence highlighting its benefits for patients with central sleep apnoea (CSA).

The value of registries in ASV

Although randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are useful to assess safety and efficacy of a therapy, the lack of diversity in the selected patient population can lead to gaps in clinical knowledge.5 Real-world evidence, such as registries, assess outcomes in a non-selected population, representative of the day-to-day reality of sleep clinics. Following this logic, FACE6,7 and READ-ASV8 have provided valuable new insights.

READ-ASV registry: indications and benefits of ASV in real life

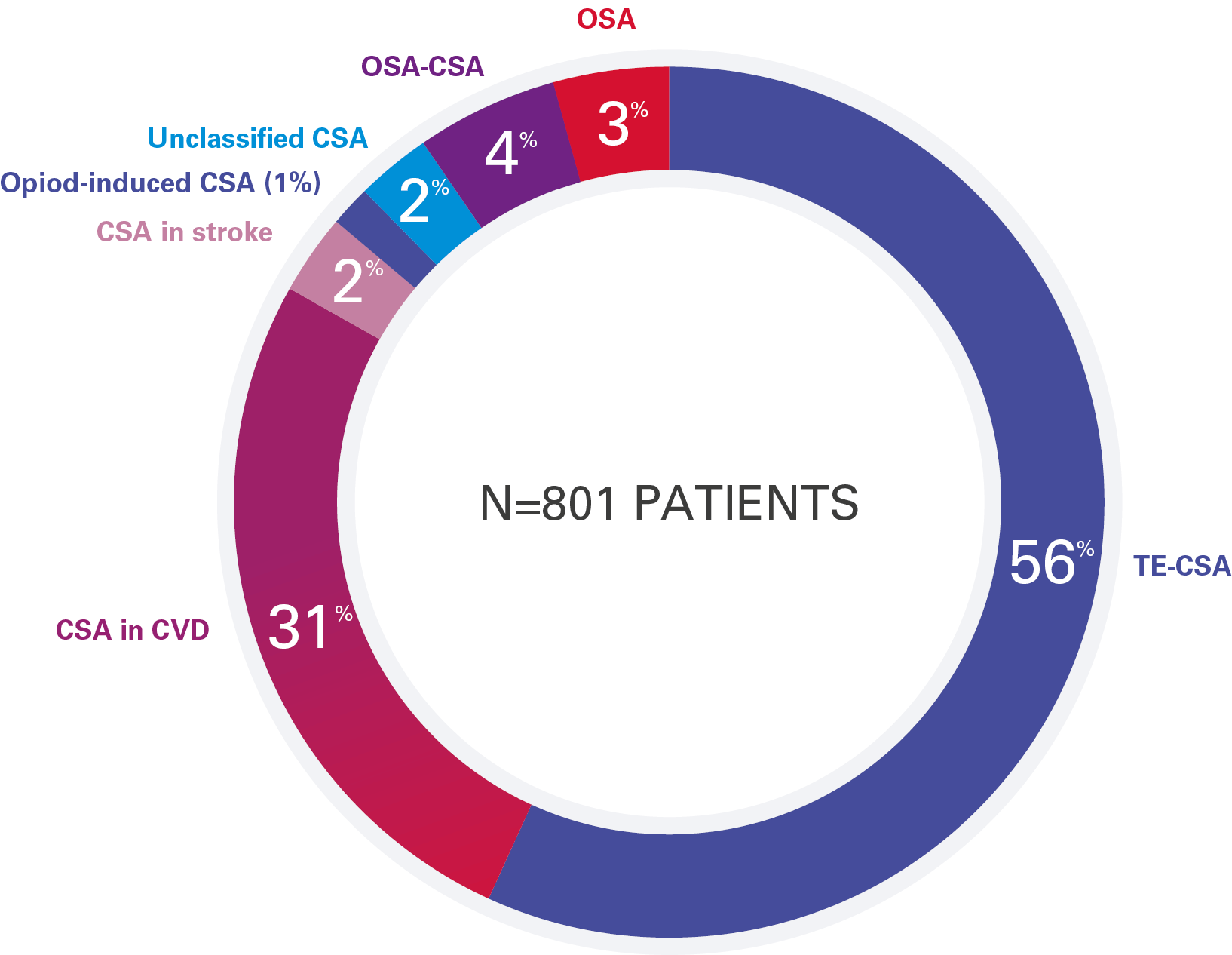

READ-ASV 8, launched in 2017, looked at the clinical benefits of ASV therapy in 801 patients in real-life settings.

The findings from the READ-ASV study8 reveal that ASV therapy is primarily used in clinical practice for patients with treatment-emergent central sleep apnoea (TE-CSA) and CSA with cardiovascular disease.

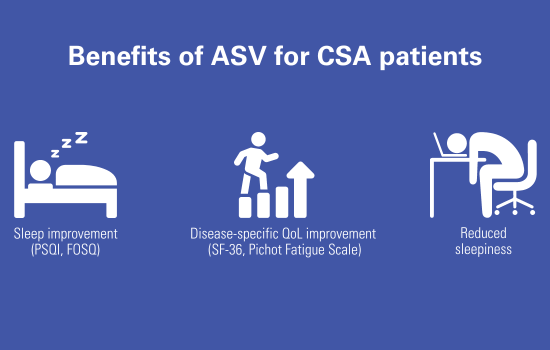

These patients experienced symptoms such as impaired quality of life, sleepiness, and low sleep quality, which were improved with ASV treatment, especially in individuals with pre-existing sleep disordered breathing (SDB).

What does real-world data tell us about ASV?

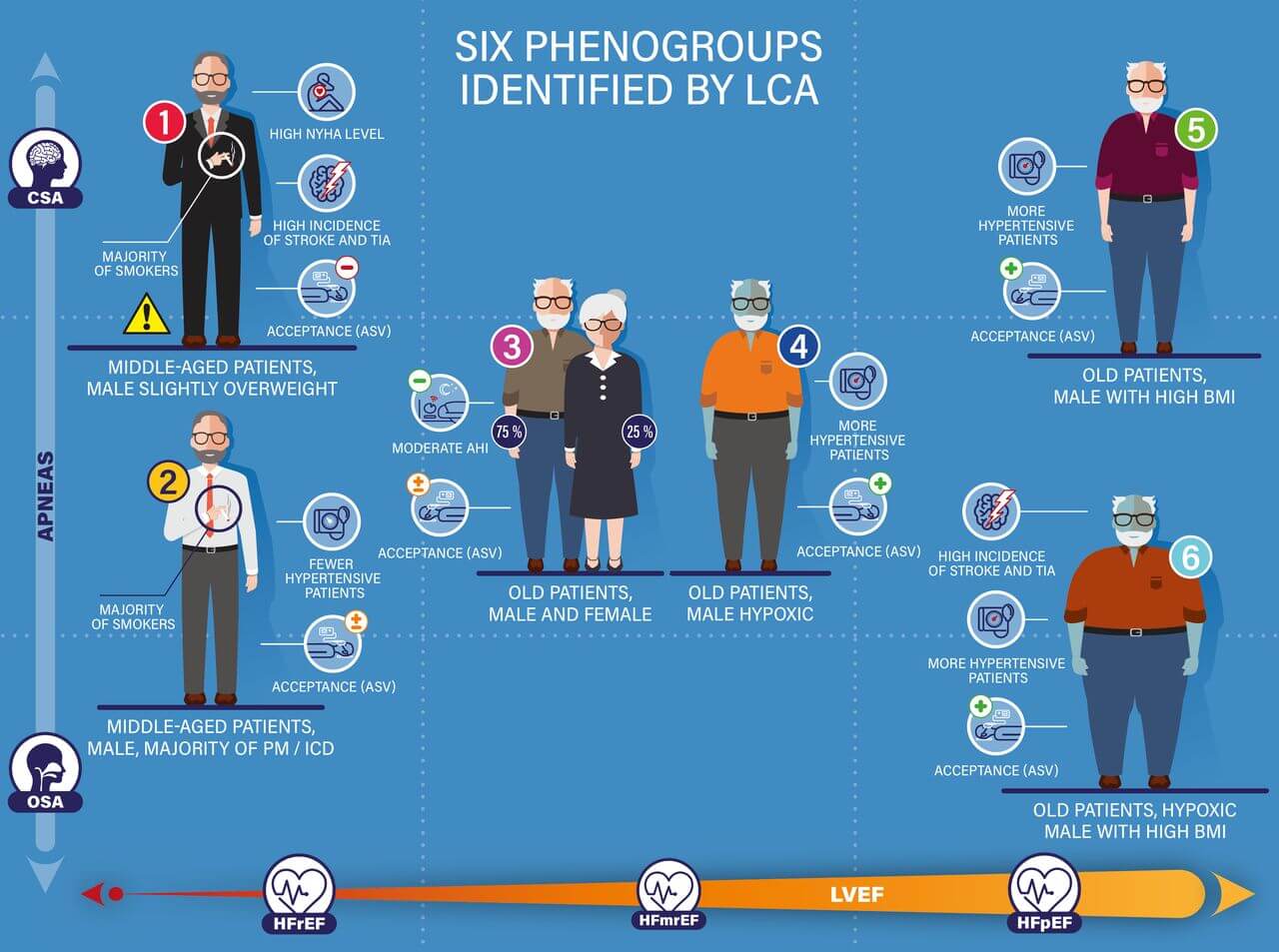

Real-world data from the registries6-8 confirm that ASV therapy is safe and beneficial for quality of life and quality of sleep in the most prevalent phenotypes of symptomatic CSA and TE-CSA and combined OSA/CSA patients. In addition, major benefits were also reported in patients with combined heart failure with preserved LVEF>45% and CSA.6,7

These registries highlighted the importance of addressing symptomatic individuals with SDB, and demonstrated that the effect of ASV can vary significantly depending on the phenotype of patients. One size does not fit all in the CSA population: careful patient selection and phenotyping should be performed to ensure ASV is prescribed to patients most likely to benefit from therapy.

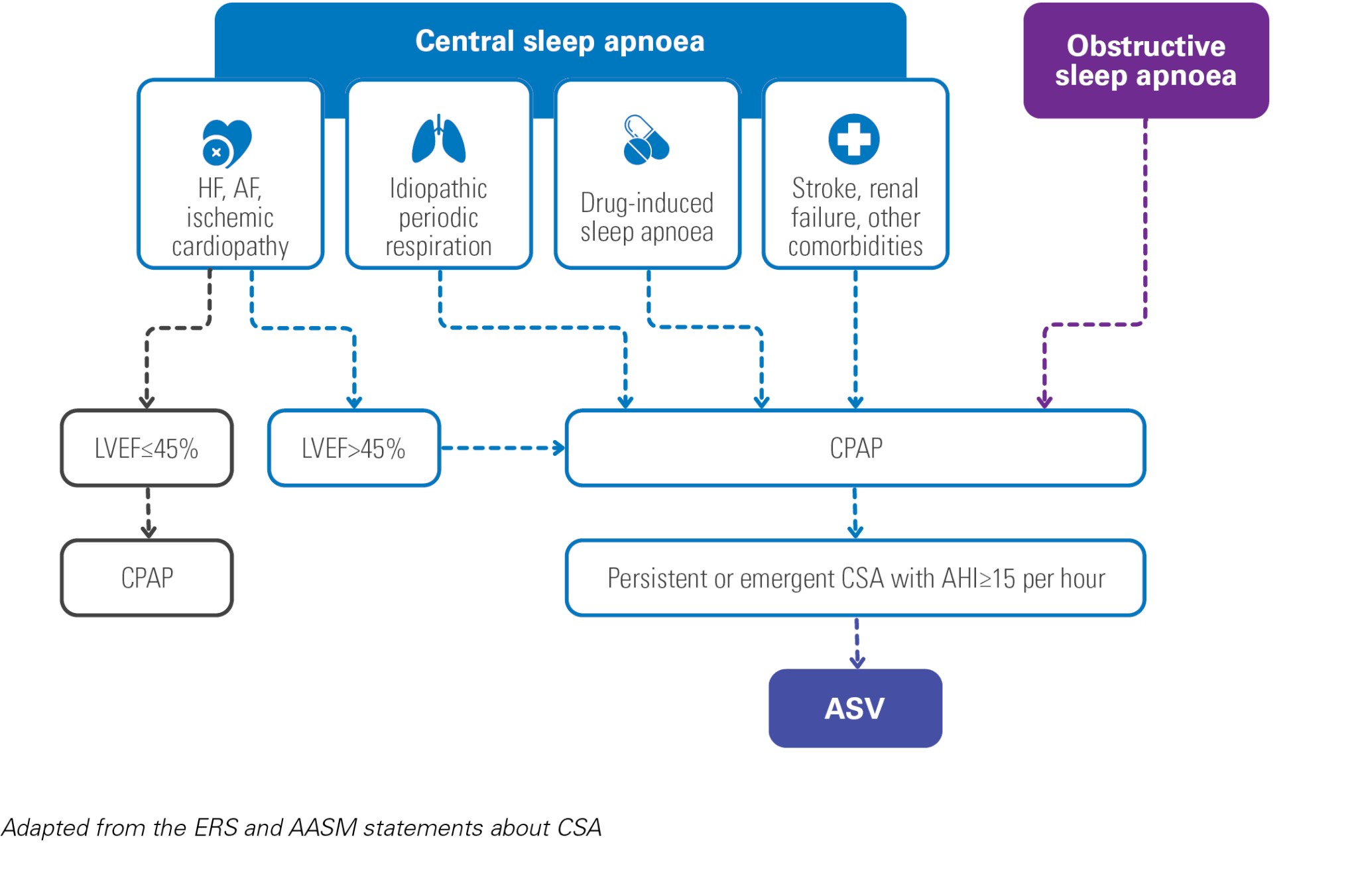

Identifying CSA patients using CPAP and switching them to ASV

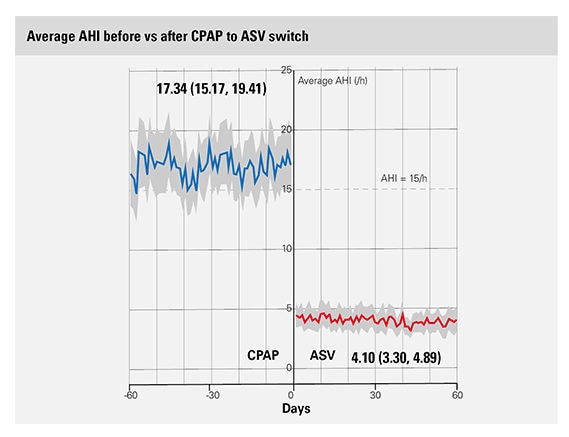

An analysis of a PAP telemonitoring database identified three categories of CSA during CPAP treatment, all of which reduced therapy compliance and raised the risk of stopping treatment. The study revealed that transitioning patients from CPAP to ASV, particularly those with lower CPAP adherence possibly due to treatment-emergent CSA, resulted in enhanced adherence and device utilisation, along with a reduction in the apnoea-hypopnea index.

This content is intended for health professionals only.

References:

- Cowie MR & al. Adaptive Servo-Ventilation for Central Sleep Apnea in Systolic Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015 Sep 17;373(12):1095-105

- Randerath et al. Definition, discrimination, diagnosis and treatment of central breathing disturbances during sleep ERJ 2017 49: 1600959 https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/49/1/1600959

- Launois Rollinat & al. Consensus français sur les syndrome d’apnées et hypopnées centrales du sommeil (SAHCS) de l’adulte. Préambule : contexte et méthodologie utilisée, Médecine du Sommeil, 2024, ISSN 1769-4493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msom.2023.12.191

- Randerath W, Baillieul S, Tamisier R. Central sleep apnoea: not just one phenotype. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33(171):230141. DOI: 10.1183/16000617.0141-2023

- Reynor A, McArdle N, Shenoy B, Dhaliwal SS, Rea SC, Walsh J, Eastwood PR, Maddison K, Hillman DR, Ling I, Keenan BT, Maislin G, Magalang U, Pack AI, Mazzotti DR, Lee CH, Singh B. Continuous positive airway pressure and adverse cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea: are participants of randomized trials representative of sleep clinic patients? Sleep. 2022 Apr 11;45(4):zsab264. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab264. PMID: 34739082; PMCID: PMC9891109.

- Tamisier R et al. FACE study: 2-year follow-up of adaptive servo-ventilation for sleep-disordered breathing in a chronic heart failure cohort. Sleep Med. 2024 doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2023.07.014

- Tamisier R et al. Adaptive servo ventilation for sleep apnoea in heart failure: the FACE study 3-month data. Thorax. 2022 doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217205

- Arzt M et al. Effects of Adaptive Servo-Ventilation on Quality of Life: The READ-ASV Registry. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024 doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202310-908OC

Last update: 06/2024